A psychological blend of fantasy, dystopia, and mediaeval makes for an instant classic in prog-rock opera.

4.9/5

Once one of the more interesting names in the new explosion of underground British music acts who emerged from the late 2010s, HMLTD stood out for their artsy tastes. Their debut West of Eden was released in 2020 with positive reviews for the use of glam rock and a knack of creative twists on post-punk. However, the album is sandwiched within a good line of strong contemporaries. Between the debut album sees black midi’s Schlagenheim and Black Country, New Road’s For The First Time be released respectively in 2019 and 2021 which rockets the two bands to a lot more adoration.

With tightening competition from Squid’s krautrock-based sound, Dry Cleaning’s spoken-word wit, and Yard Act’s satirical attack on capitalism, HMLTD came off as tame. Their music was acknowledged as well-constructed with a punchy sense of rhythm, but it falls flat in establishing what makes the band great. Meanwhile their gender-bending aesthetic is seen as even offensive in the case of the LGBT+ community due to the sense of appropriation. It’s time to go to the drawing board; there needs to be a way for the band to stand out from all the others.

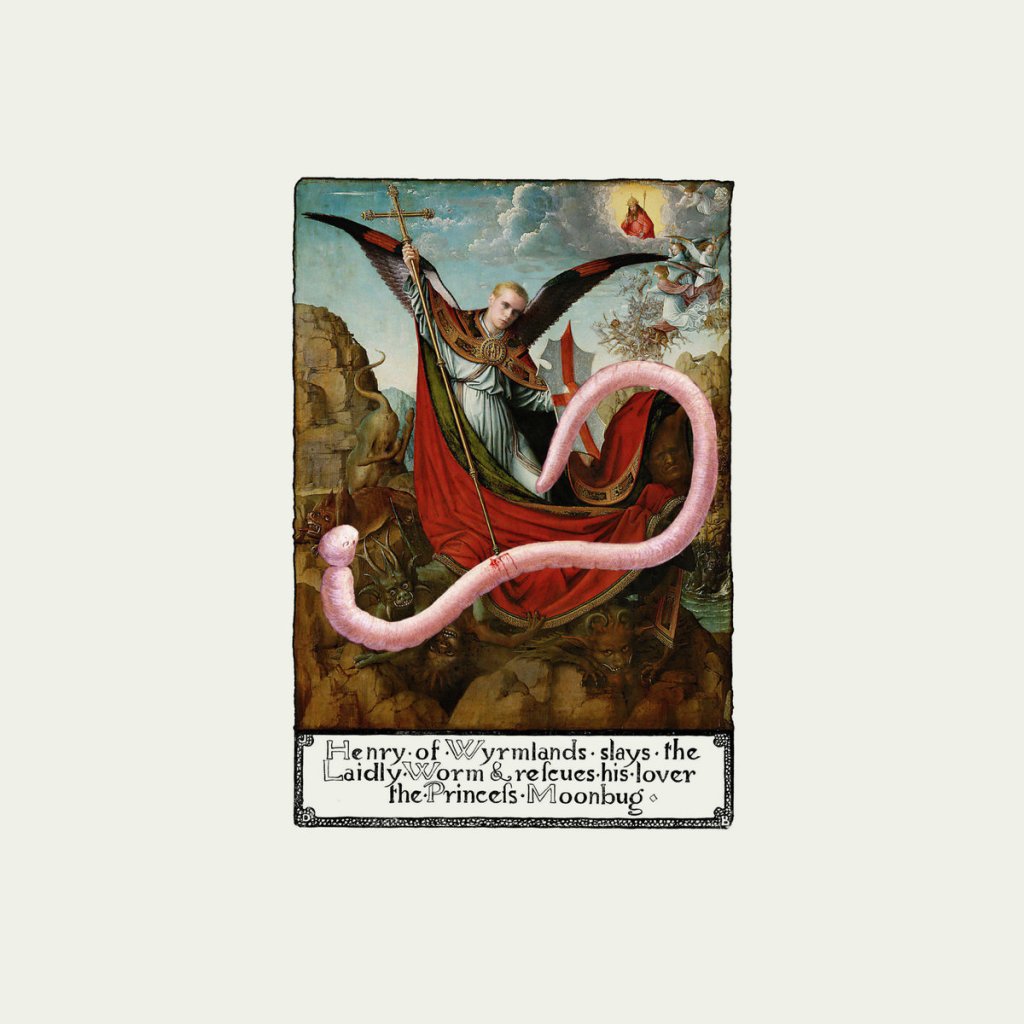

Thus births the arrival of The Worm, finally out three years after the band’s first studio record. The album’s Bandcamp page describes it as being “less a concept album than a fully-fledged musical universe, transcending genre and medium.” On Clash, Frontman Henry Spychalski said that the album was conceptualised in parallel to how depression and anxiety is symptomatic of Britain’s air of hopelessness. So, what’s the deal with the sophomore effort’s content? It’s built around a fictional, Mediaeval version of Spychalski who attempts to rebel against the worm-run authority in England with all the epicness and twists that comes with it.

Compared to West of Eden, to start off with ‘Worm’s Dream’ would be akin to greeting an acquaintance who’s into Chess only to get an uppercut to the face. The choir-like vocals from the backing singers, without any instruments, sung of an aftermath of an uprising against a giant worm (yes, that’s the inference). The crescending volume of the voices that culminates in the unexpected barrage of a guitar and the drum makes for a crazy introduction for the best. While it presents a veneer of ambition like black midi’s Hellfire, the few lines already hint at a larger picture, that of a near-apocalyptic war between humanity and the worms.

Enter ‘Wyrmlands’ which establishes the Darwinist lifestyle of the worm-run England with a linear song structure, a riveting guitar riff, and a hazy vocals from Spychalski. The theatricality might be a challenge for many, but the way that every note, echo, and even mixing adds to the story makes for an immersive experience. ‘The End Is Now’ emerges out of the blue with a vintage sample (or is that just the production?) for a Hamilton-esque entrance of our main character. Proclaiming himself to be born ‘At the fall of the vertebrate government’, you quickly get hooked into the fictitious Spychalski’s backstory as he sets himself up as a bastion against tyranny. The piano, an instrument that the band doesn’t seem to use much of prior to The Worm, is expertly used as a stage direction-like guide to navigate the world that we enter as noted in ‘Days’. A ballad that initially reminisces about the misery from Spychalski’s sacrificial abandonment of his love life, the minimal instrumentation and downtrodden feeling is a foreshadowing hint for what’s to come later…

With a dip into anachronism, ‘Saddest Worm Ever’ comes out with a bang with the most punk-like sound that HMLTD has ever delved into with a catchy hook and a crunchy guitar use. In a Bond-like swagger, the drumming adds a good sense of groove to refrains like “Like a gun to the head” or “Power gets you high” as we dive into Spychalski’s inability to bow down to the worms. It’s an evocatively fun way to not only understand the gravitas of resisting the worms, but to see the parallel that peers through in being a “worm child” in relation to power is revealing. It suggests a deranged, even obsessive drive that Spychalski has in his rebellion especially as the leader.

Thus, as the track ends with a declaration of execution against consuming worms as an act of protest, we’re treated with an instant cut to ‘Liverpool Street’ – and we’re treated with the plot twist of the album. With an instrumentation that echoes back to ‘Days’ (in a more prog-pop style that is), we learn that Spychalski has created the world that the album is purportedly set in to deal with his mental illnesses. While the lyrics there suggests that the instigating event behind his breakdown is that of his relationship crumbling, the subtext of The Worms being built around anti-authority and societal collapse hints at an optimism that is lost. While the antagonists have always been the worms, snippets of lines like to link people with their oppressors. Thus, to learn that the worm was not only conceptualised as a threat in Spychalski’s imagination, but holds a spiritual significance to him tugs us into the spine-chilling revelation of what needs to be done. “He has to kill the Worm.”

Now, we’re treated with the central theme of the album at its clearest; an all-consuming need to go beyond our vices and personal demons no matter how endemic it is in our homeland. With Brexit leading the UK’s politics to splinter into extremes over topics like trans rights or immigration, it all makes sense as to why worms are so big as a symbol. As the title track shows with an amazing instance of vocal harmony for the chorus, humanity and worms are intertwined in a vicious cycle of destruction, toxicity, and denial. Thus, to blame our faults on the worms when they’re insignificant in reality alludes to our prospect of deflecting responsibility around societal collapse. In other words, the worms are emblematic of our sins that were apparent to each one of us since they’re supposed to be within us. However, we instead ignore it in favour of blaming their presence on others by pointing out the worms that were residing in them.

‘Past Life (Sinnerman’s Song)’ has a nice postmodern interpolation to Nina Simone’s most well-known cover song through its piano in the beginning. From there, Spychalski abandons his warlike coup against the worms in favour of becoming a messiah for his kind instead, advocating for self-thinking, hope for the future, and perseverance. While there’s a line about holding hands to defeat the worms that might come off as corny, the whole track feels utterly epic in its right. You can sense the pulsating build-up to the declaration of being saved by Christ which is a humbling twist compared to the first half of the record. It’s such an immaculate listening experience that, in contrast to ‘Saddest Worm Ever’, the ending monologue concludes with an affirmation of loving life itself. It’s simple, yet poignant in its placement as it dispels the universe that The Worm has revolved itself around in all but two tracks.

To finally cap off the album, ‘Lay Me Down’ eschews most of its rock influences in favour of being a progressive/chamber pop conclusion. The most conventionally pop song here, the album ends not with a recap of what its story is or even where it ends, but rather on what the moral is. “I’ve got no end / Lay me down / My only friend” is an open book which captures the two key opposites. On one hand, it’s a stoically Christian reminder of living your life in contentment as we continue to work on being our best self every day. On the other, it’s a beautifully bittersweet ending that shows appreciation to what we have on our lowest point or even on our final breath. The guitar solo in the end marks the ordeal done as we’re left with only silence after the album is completely over. No matter how problematic our life is or how terrible everything feels, it never hurts to try and improve with the time that we have. It’s what makes life worth fighting for.

Simply put, The Worm is a near-masterpiece for how far it pushes its boundary as a rock opera project. Its theatricality in general might make the album daunting for casual listeners to get into for how ‘deep’ its themes can be, but the experience is well worth every second of your time. If HMLTD seeks to be recognised on the same level as the likes of black midi or Black Country, New Road, then they might have truly done it here. This album will most likely be looked at as a standout in the next years to come especially from fans of avant-prog music. Treasure it while you can.

Leave a comment