Few albums have heralded the fall of mainstream excellence like the country/popstar’s latest disses and wangst.

A diva first, a homegirl after. Modest in her looks, but rich in gold. Relatable lyrics, extraordinary lifestyle. Progressive views, regressive ties. Over nearly a score’s worth of her career as a mainstream titan, Taylor Swift has formed an image that is both transcendent in its reach and fragile in its contradictions. Her first few albums set her up as a girl-next-door prodigy in country pop whose lyrical themes of break-ups and romance often lend memes about her boyfriends. Her 2010s output saw her transition more towards electronic beats and dance-based rhythm with more flummoxed reactions from her devoted Swifties although they soon got used to it. Sort of.

The star is without her lists of complaints and criticisms from those who find her fandom almost cult-like and her representation manufactured from the ground-up. Her parents work as executives and had named her as such due to its marketability. Her themes that set her up as being unfortunate or miserly came off as being whiny especially as her commercial success became more apparent as the years went by. Whatever justifiable feud she might have with someone like Ye once fell off the wayside when she began to release remakes of her previous albums in response to other artists’ successes.

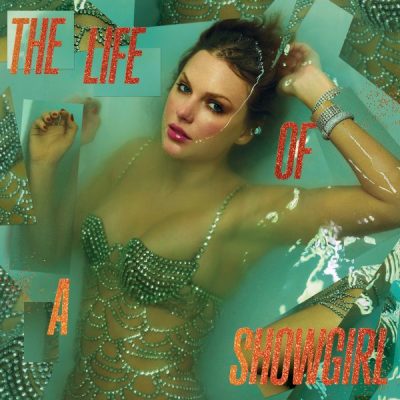

All that is hinted in her 2020s catalogue aside from her more serious efforts in Folklore and Evermore in 2020 are out in the open with the release of The Life of a Showgirl – a concept album which revolves around banging your football-playing (the American type) boyfriend, dissing contemporaries for perceived slights that at best a long shot compared to what is intended, and bemoaning about the billionaire lifestyle. It’s an embarrassing sort of affair in that the very identity had collapsed on itself. The “nuances” that supposedly made Swift an icon in the first place gets vacuumed in to leave one spiteful husk of a figure who has all the blitz and the glitz in the world without the imagination to make full use of it. Let alone the comprehension to acknowledge why they’re there in the first place.

Never mind the glamour in the guitar riffs in ‘Wi$h Li$t’, the vocal layering in ‘Honey’, or the reverbs in ‘Opalite’. Behind the attempts made at making the instrumentation lush is the acquired narcissism of a diva who, unlike the child actor from the 1997 animated cult classic Cats Don’t Dance, has never been given the ounce of opportunity to get humbled. Too many of her symbols, metaphors, and allegories demand that they be solely read from her own experiences, her own perspective, her very self.

A glaring example is ‘Elizabeth Taylor’ where Swift compares her much-covered relationships with the famous Hollywood actress from the 1930s. She relies on the comparison to present herself as a girlboss; someone whose seductive allure makes a shield that makes her hard to take control of. This feels hollow. Both because we expect her to cover it to the point of redundancy and because she released the album in the time when the sociopolitical climate in the United States is nudging toward the return of the obedient housewife status quo. There are no commentaries made around the sexism or the extent to which the eponymous film star’s dramas have made her a product of her time. It’s like Katy Perry’s recent attempt at making a comeback from last year. However, kudos could at least be given to Perry for trying to make a comeback in the first place. ‘Elizabeth Taylor’ completely whiffs at its potential and didn’t even once recognise the more dangerous similarities that necessitate improving the treatment of female celebrities.

A similar problem happens in ‘The Fate of Ophelia’ in that Swift makes parallel her hinted love for her fiancé Travis Kelce to Ophelia’s devotion to Hamlet in William Shakespeare’s famous tragedy. Yet, Ophelia’s no stranger to scholarly analysis and even some controversial critiques over her minimised role as a female character whose loyalty endures even as Hamlet abuses her during his descent to obsessive vengeance. It’s not to say of course that Swift’s relationship with Kelce is actually more complex than what reports suggest. What it does call into question is the “why” part of the comparison. If you were to replace Ophelia with another female figure like Cleopatra, Lady Goldiva, or Marie Antoinette, outside of a few changes in selected words, would the song’s meaning fundamentally change?

Could that be used to juxtapose Swift’s complicated image to the little time she spent with Kelce? Maybe given the complex, open-book nature of Shakespeare’s play, it could bring into mind how the fandom inserts or projects their expectations into Swift’s personal life. Could it even be that the topic of Ophelia was chosen because she was a part of Shakespeare’s long line of prominent female characters who are doomed to death and Swift, a fan of some of the playwright’s works, wants to object to such a fate? The answer is most likely no, at least not since the honest little banger that is ‘Love Story’. Because that would threaten the fabrics of what she modelled herself as to the whole world by risking isolating a sizable part of her fandom in favour of actual authenticity.

It would be funny to label her a caricature of the many vapid celebrities that exist in our lifetime if not for the reality that she uses her reputation to tear down on the likes of Charli XCX. Someone who, despite being on the upswing as a megastar, wrote songs that dealt with the actual difficulties of being famous. Friends are less valued so much as feuds for entertainment, privacy must be decrypted to be updated on every waking second, even songwriting now must have an autobiographical touch regardless of whether it’s too personal.

Actually, that’s what ‘Actually Romantic’ deals with in the worst way possible. Swift makes subliminal disses against Charli by portraying her as an envious snake who wittingly smears Swift all the time to make herself look better. Those who actually listen to the original song, ‘sympathy is a knife’, will know that it’s about how the pressure for success damages the self-esteem of female artists by mentally forcing them to think of themselves as needing to be better than others. People who listened to brat will go a step further and note that one of the key themes that make the album one of the best pop records of last year is on how mainstream expectations can fracture the bond between those same artists as noted in ‘girl, so confusing’. The reality is that the supposed obsessed rival actually made a reference towards Swift in context to her anxieties and crumbling under public pressure.

‘Actually Romantic’ is fucked up in its reference because by going after Charli whose focus is on self-introspection, Swift shows little interest in thinking about her flaws and shortcomings. There is always that one person who wants what she has. There will always be that one group who are rooting for her downfall because they’re unable to accept her success. Swift previously alluded to it in her 2017 album reputation with some of the most divisive reviews in her career then. Now, she has the gall to use the same line of attacks against even an artist who commands respect both from the mainstream and from the broad alternative music community for being willing to be herself. Unless she gets an album out that performs so poorly in terms of chart placement that she needs a re-evaluation of her artistry, Swift may never understand why being authentic is an invaluable part of being a music artist to the whole stage.

If you manage to get to this paragraph by now, let’s say that the three tracks alone would be a good enough reason for you to stay away from The Life of a Showgirl. It’s a vapid exercise that’s filled with the self-pitying of a spoiled princess who is so high up in her tower that she looks down at her people like ants. The rest of the albums consist of shiny production that only accentuates the pettiness of lashing out against perceived foes while bragging about your fiancé or your ivory crown. Its pristine exterior only masks the reality of its shamelessness that is deserving of being compared to even Lil Pump’s sordid sophomore album. Even the Shaggs have more heart in their adolescent trauma than Swift does in her 35+ years of living as one of the biggest names in the world.

If you’re a Swiftie who stumbles upon this random blog post, may I at least add in the end that there are several music artists that are worth looking into. For a start, Adrianne Lenker is easily one of the best American singer-songwriters whose literary style of lyricism makes her break-up songs more pained than even the best of Swift’s. ‘sadness as a gift’ is one classic example where the Americana guitar playing compliments the metaphor of the four seasons as the deterioration of the relationship. Among her finest written is from her band Big Thief’s acclaimed work Dragon New Warm Mountain I Believe in You called ‘Simulation Swarm’; an impressionistic free-verse poetry exercise that appears to allude to her long-shot wish of reuniting with her twin brother whom she’s separated from since birth.

Another artist to check out is Vashti Bunyan, an English singer who initially rose to fame in 1970 with the release of her debut Just Another Diamond Day. The title track has a nuanced, yet fantastical atmosphere in its flutes, vibrato violins and gentle guitar playing which befits the nursery rhyme-like simplicity of the pastoral life. It would take more than 30 years until she finally became famous for her work which was then followed up with her second album Lookaftering in 2005. One of the tracks in the record, ‘Here Before’, encapsulates the bewilderment of childhood that contrasts with the newfound responsibility of being a parent which foreshadows the child’s eventual growth that will put them in the same situation as their own parent.

Lastly, as a poppy alternative, Magdalena Bay is making waves as one of the most inventive duos of today. Their second album Imaginal Disk could easily be seen as the vanguard of how you can still make catchy tunes without needing to smatter it with choruses and refrains to get people to remember the song title. ‘Death and Romance’ is a fan favourite for its vibrant maximalism that incorporates synths and riveting live drumming that ebbs with the tempo. My favourite would have to be ‘Tunnel Vision’ for its angelic chorus delivery, futuristic sense of production that makes the song structure fluid, and its very daring switch in genre for a solo guitar performance in the outro. Never one to settle down, the two deserve many of the praises that their fans would heap at them. Poptimism itself now is on its life support as commercial viability now seems too constrictive to one’s creative freedom.

Leave a comment